A new and original angle on one of the great unsolved mysteries of archaeology: the Vitrified Forts of Scotland.

The mystery of the vitrified forts has challenged, and defeated, generations of archaeologists and historians. Despite the sheer volume of theories and explanations in countless learned papers, which might themselves be enough to build a small fort, there is still no consensus as to when, how, and why this primitive and resource-intensive technology was employed. This article presents a new, speculative and previously unpublished theory, based on deduction from simple observation of experiments on the workbench which had unforeseen consequences.

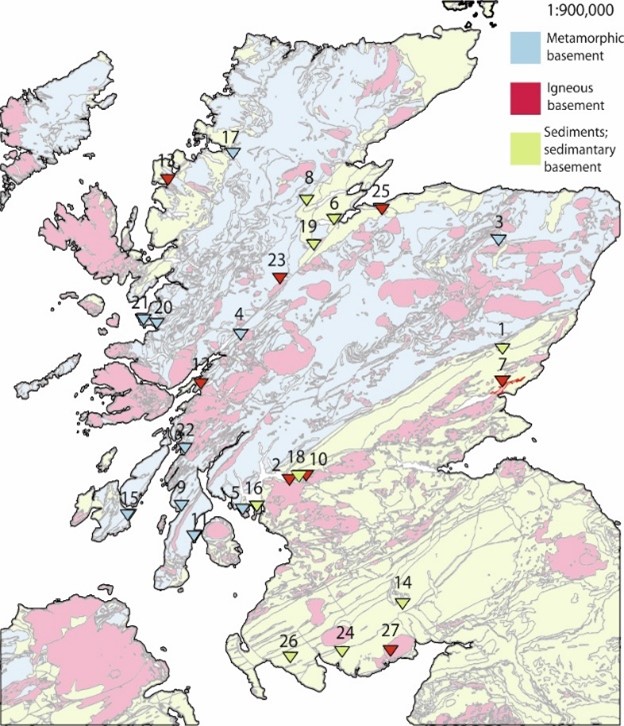

The phenomenon of vitrification can be described easily enough: certain hill forts, (about 400 of which are located in Scotland with relatively few elsewhere) dating back to the Iron Age, were constructed of immense stone ramparts, up to 15 feet thick, and interlaced with large timbers in a form which Julius Caesar called ‘murus Gallicus’ or ‘Gallic walls.’ At some point after construction part of the wall (very rarely all of it) was heated to at least 1000 degrees centigrade, so that the surface of the stone vitrified – it melted and when it cooled down again, it had become glass-like. On sites where these walls are still standing, the vitrification has fused the stones together into a more-or-less solid mass, and the internal timbering inside the wall has burned away, leaving vitrified surfaces right through to the inside. On sites where the walls have collapsed, lumps of vitrified stone can be seen in tumbled mounds

Several laboratory experiments and reconstructions have been carried out in attempts to provide firm data about the processes required to achieve this effect. Attention has focussed on the local geology and the size and type of stone, (in particular the silica content) and the methods employed to produce the temperatures required to produce vitrification.

(1985)

In general the data produced has been so variable that they point to no certain conclusions. Dating by thermo-luminescence and radio-carbon have produced dates so inconsistent with each other, and so inconsistent with the archaeological evidence, that there is still much doubt about the methods used, and even more doubt about the function and purpose.

Three competing theories have emerged from the evidence, but after over 200 years of study, all have their problems. They can be summarised as the defence theory, the attack theory, and the status symbol theory.

The defence theory suggests that the vitrification was a deliberate part of the construction, intended to fuse the stones in the walls together and make them harder to tear down. This theory fails on several points. Most forts only exhibit localised vitrification on certain parts of the wall, limited vertically and horizontally. In some cases vitrification extended to most of the wall, but never to all of it. Sometimes the base of the wall was unburned, sometimes the top of the wall was unburned. Experiment showed that even where timber interlacing was burned inside the wall, the vitrification did not usually penetrate deeply enough below the surface to have a significant effect on the structural integrity. If it worked as way of strengthening the wall, why not vitrify the whole wall, and if it did not work, why bother with any of it?

The Experimental Production of The Phenomena Distinctive of Vitrified Forts.

V. G. Childe and Wallace Thorneycroft 1937

http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-352-1/dissemination/pdf/vol_072/72_044_055.pdf

The attack theory suggested that the walls were burned during warfare, either during an assault or as a ‘slighting’ after the fort was captured, and that the walls were weakened not strengthened, by burning. The intention was to destroy the walls by fire and to smoke out the occupiers by burning through the structural timbers. This theory fails to take account of the resources in manpower required to harvest enough good big timber and then dry it out enough so that it would burn for long enough and hot enough to reach the desired temperature, over the several days needed to heat the stone up to melting point, and then to destruction. A warband would have to travel to the site and find a supply of timber, then cut it, guard it for at least a year while it air-dried, and then transport it and stack it against the walls and wait for enough wind from exactly the right direction the create the draught to burn through the structural timber in the wall. With the manpower and the time taken to do all that, the wall could have been torn down by hand, or the defenders could have been starved out, with no need for the elaborate firing.

The status symbol theory has come to the fore along with the post-modern trend to see the whole of pre-history as a struggle for power between rival classes. There are some more-or-less convincing arguments that many ceremonial weapons, and even the forts themselves were not in fact military or defensive in purpose, but were symbols of power. The ‘status’ theory did not appeal to me, as being contrary to common sense, and going against the historical accounts of warfare in which the development and employment of lethal weapons, fortifications, sieges, defensive walls and destruction of entire cities are so commonplace as to be normal. In the case of vitrified forts, the only argument presented to support the idea that status could be gained by melting an area of the fort wall was the size and spectacle of the fire, and the novelty of seeing stone turn to glass. Neither was convincing to me, because the builders were already masters of smelting technique, so their metal weapons would be a more intimidating and immediate demonstration of power and status than glazed rock, and the idea of setting fire to a small part of your own dwelling in order to demonstrate some kind of superiority seemed irrational and perverse, and certainly not sufficiently convincing to be copied 400 times by the neighbouring tribes.

After I visited a vitrified fort, and carried out some experimental work however, I got a shock. I changed my mind about the status symbol theory, and this article explains how and why, and presents a new theory of why vitrified forts exist. The article is intended as a spur to others who have greater scientific and archaeological knowledge, and more resources of time and money than I can bring. I believe that my theory can be proved or disproved in a few days in a basic workshop, and if the signs are good, full scale experiments can be carried out on as many sites as necessary to put the matter beyond doubt.

My story begins at The Doon of May, an Iron age hill fort by the machars near Whithorn in Galloway. The site was planted with trees up to the edge of the ramparts by the Scottish Forestry Commission, and purchased in 1999 by far-sighted, independent minded activists (The Tinne Beag Workers’ Co-operative) who manage the woodland for sustainable use of timber and non-timber forest products, and who have established a low-impact community intended to revive Scots Celtic culture, politics and ideology. I had been interested in vitrified forts for many years and had accumulated enough books and papers on the subject to know my way around the basics. I heard about the Doon of May from a friend, and in the spring of 2010, I travelled there, introduced myself to the community, and stayed for a few days, mostly sitting round the fire singing and playing the bagpipes.

Some months later I was invited to play the pipes for the summer solstice celebrations. We climbed the steep ramparts of the Doon and camped out round a good stick fire for a ‘white night’ of music and conversation. As the sun was coming up, I was in conversation with Jeff, the owner, and asked him if he had any favourite theory about how and why the walls around us had been vitrified.

“I do”, he said. “Do you?”

I explained at some length about the three prevailing theories among academic archaeologists and asked him which one he favoured.

“ Och – none of them. “

“What do you think it was, then? Do you know?”

“I do” he said.

“What then, tell me.” He leaned closer, looked round him as if to make sure no-one was listening and whispered in my ear… “Dragons!” he said, and screeched with laughter.

There is no evidence at all for dragons in Galloway, fire breathing or not, but there is very little convincing evidence for any of the three academic theories, so his joke was not as ridiculous as it might sound. As it happened it resonated with me, because one of the aspects which interested me about vitrified forts was the occurrence in the oral tradition of folk stories about glass towers in a wood. (For example The Sea Hare, [a] or The Glass Hill, [b] )

[a] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sea-Hare

[b] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Princess_on_the_Glass_Hill

Oral history and culture – some of which may be older than any literature, – can sometimes fill in gaps in written history with remarkable accuracy. The builders of the great megalithic observatories carried detailed astronomical knowledge in their heads, likely to have been accumulated over generations, and there are several cases where local knowledge of fairy stories about a warrior buried under a mound were shown to be essentially correct several thousand years later when they were excavated. I paid little attention to the idea of dragons, but thought it likely that the answer to the mystery would lie ‘outside the box.’

The conversation with Jeff prompted me to take a closer look at the vitrified walls of the Doon of May, and I walked right round it a few times, trying to identify possible entrances, and looking for areas of vitrified wall still standing. I found quantities of vitrified stone, which had tumbled down sometime in the last 2000 years, and now lay in grass covered piles of rubble. A little scratching up turf with my hands produced a couple of pieces the size of large potatoes, and I put them in my bagpipe case as souvenirs of a great and memorable night of music.

I did not get home for another 10 days, as I had a tour of festivals and venues where I was booked to play. I forgot about the rocks of Doon until I unpacked the truck. I put the lumps of stone by my hearth, where they stayed for several weeks, until I had time to settle down and do some more reading about vitrified forts. After finishing the book at about 10.00 in the evening, I decided to try an experiment and took the stones out to the workshop. I laid them on the bench and fired up a propane gas blowlamp. I tried heating the stones in different ways, not particularly methodically, but using different parts of the flame at different temperatures to see if I could melt the surface. Sure enough after a little while the surface began to shine, small droplets of melted rock formed, and ran down the surface, where they immediately cooled and solidified, leaving a shiny glazed surface. I tried it a few more times, and it was clear enough that melting the rock was no big deal – it could be done easily enough, more or less at will, using modern domestic equipment. I went to bed, thinking it all over.

The next morning I went back into the workshop. The stone was on the bench where I had left it. I picked it up to look closely at last night’s work – and immediately dropped it, as if it had burned me. But it was not hot, it was stone cold. It was not heat which made me drop it, by instinct or reflex action, but an electrical charge. Static electricity. I realised in that moment that I might have the answer to a mystery which I had been turning over in my mind on and off for years. Maybe it was all about static electricity?

In great excitement, I repeated the procedure, and after several attempts I was able to reproduce the effect, although not as strongly as the first time. The lack of repeatability was possibly because I was expecting it, or possibly because the capacity to hold a charge was reduced by repeated heating, or maybe because my own body was less sensitive on the later attempts.

So this is my outline of a new theory behind the vitrification of stone forts in order to accumulate static electricity. It is a speculative theory and needs to be proved or disproved by hard evidence, but the theory does provide a rational explanation for some of the mysteries surrounding the subject. It provides for a display of power and status by an elite priesthood, to create shock and awe in the minds of neighbours, enemies or as part of an initiation ceremony, and it might account for some of the more anomalous findings of the archaeology.

The basics of the theory can be set out easily enough, although the possibilities for speculation are endless. Each part of it would need to be tested experimentally to see if the theory will stand up, but here are some of the ingredients, which should be seen as pointers for further investigation.

- The stone was vitrified in order to create a static charge, which would cause anyone who recieved the shock to immediately let go of the conductor, by reflex action.

- The ancient Greeks were aware of static electricity in the early Iron Age. In about 600 BC, the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus discovered that amber can develop the ability to attract objects. The word electricity is derived from the Greek word for amber.

- Contemporary science has still not fully explained the phenomenon of static electricty, which is caused by an exchange of electrons between different substances (triboelectrification.) Both heat and light have been investigated as possible factors.[1]

- Only one section of vitrified wall would be needed to create the effect. The heated stone would have to be off the ground and electrically insulated from the earth, which would explain the ‘raft of timber’ below the vitrified area which Julius Caesar described as murus gallicus, for example.

- The location of the verified area could be anywhere on the walls of the fort – on a cliff edge, or overlooking the sea, or by the main gate of a fort, or hidden in a secret area – so the spectacle, not defence, could be the objective.

- The effect did not depend solely on geology or selection of materials, although some stone is more suitable than others, both for vitrification and for sproddcinbg static electricity. [2]

- The reaction to a static electric shock sufficient to make a person drop the charged stone, or release a metal conductor set in the wall, is an instinctive, reflex action. It does not depend on strength, fighting prowess, or privilege. The effect could be repeated by re-heating the stone.

- In the context of a challenge against ‘super-natural’ power, an unexpected static shock would impress enemies, novices or initiates.

- One possible scenario might be a ceremony in which the person they wanted too impress (the subject) could be given a challenge. The occupiers of the fort would claim a supernatural power which would prevent the subject from picking up or holding an object. They they would be given one chance to grasp an artefact of the revolutionary new metal (a sword?) but it would be imbued with a power which meant that they were unable to hold it and would drop it immediately. They would be taken to the vitrified area – impreessive in itself due to the glazed rock – and shown the metal object, set into the vitrified and electrically charged stone wall. They would try to grasp the object, but because they were not expecting a static electric shock, they would probably drop it immediately be reflex actiopn.

- Such a procedure would be likely to pass into folklore and fairy-tale as a mystery. (The Glass Tower in the wood, for example, or the Arthurian ‘Sword in the Stone’)

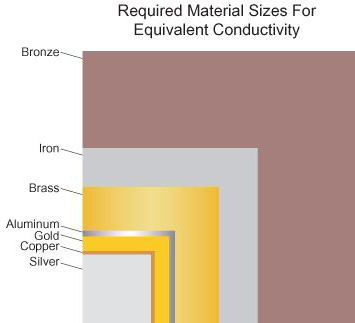

- Evidence of copper smelting has been found at the vitrified fort of Dun Deardail. Copper was one of the earliest metals to be smelted and is an excellent conductor almost as good as silver which is the best of all. The conductivity of bronze and iron are significantly lower than copper, and the small percentage of tin added to copper to make bronze, degrades the electrical performance of the resulting alloy to a far greater degree than the compositional percentage. As a result the sectional area (and hence the required volume) of an iron or bronze conductor would need to be up to 6 times greater than copper for the same conductive capacity. [3]

- Blacksmiths of the Iron Age had highly refined and sophisticated metallurgical smelting techniques, and (possibly accidentally) produced alloys of iron and phosphorous with unusual resistance to rust, as demonstrated by the 4th century CE Iron Pillar of Delhi. [4]

Thanks for reading to the end….. 🙂

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triboelectric_effect

[2] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80485-w

[3] https://www.bluesea.com/resources/108/Electrical_Conductivity_of_Materials